I’m in Montreal for the fourth International Public Policy Association Conference. On Friday I’ll present a paper as part of the provocatively named panel Public procurement: Humdrum bureaucratic beast or vital instrument for social change. My paper (draft here) looks at the role of citizen choice in delivering public services, and the ways in which this contributes to the broad set of environmental, social and economic policy objectives now attached to procurement. Specifically, I analyse the failure of two recent UK schemes which aimed to deliver large-scale but highly decentralised infrastructure: the Green Deal for energy-saving renovations, and the Verify program for identity assurance in access to digital government services. Both have been subject to rather damning reports from the National Audit Office and parliamentary committees, and both fell dramatically short of their intended scale and impact. I started thinking about the idea of citizen choice in response to recent CJEU case law on the role of contractor selection as an essential part of public procurement – in the Falk Pharma and Tirkkonnen cases. The implications of these cases have been discussed by Sanchez-Graells here and here, and by Bouwman here. Briefly, in these cases the CJEU held that schemes in which a public authority authorises all economic operators who meet certain criteria to perform a function, even where this function is paid for by the state, do not constitute public procurement. The Court held that the selection of a successful contractor was an essential condition for the procurement rules to apply. This is true even where the schemes are closed to new entrants. Given the generally expansive trend of the Court’s approach to defining the scope of procurement law, as seen in its case law on concessions, public-public cooperation and modifications to contracts, this turn is surprising to say the least (although less so when the political context is taken into account). To the extent that public procurement compliance gives many politicians and civil servants a strong migraine, contracting models which allow citizens to choose their own provider for a public service became even more interesting after Falk Pharma and Tirkkonnen. The universe of schemes which involve some element of citizen choice in the delivery of public services is extensive. Voucher schemes exist for schools, food, housing, childcare, healthcare, transport, broadband services, legal aid, training and higher education, and a wide range of environmentally or socially desirable goods and services (e.g. home insulation, energy or water saving devices, bicycles, electric cars, neutering of pets). Most often associated with the United States, vouchers also figure in public service provision in Belgium, Canada, Chile, India, New Zealand, South Korea and Sweden, amongst other jurisdictions. Potential benefits which motivate the development of voucher schemes include:

Delivering services which are more responsive to public needs

Reducing bureaucracy/red tape associated with procurement

Removing government from the role of ‘picking winners’

Reducing costs of delivering public services

Encouraging wider competition and self-sufficiency of markets

Stimulating private investment by limiting scope of government intervention

Evidence regarding these benefits in comparison with conventional procurement is limited. While a significant literature exists on voucher schemes, these are often evaluated on an individual case basis with a focus on their distributional impact, rather than their impact on the cost and quality of public services. The above list reflects an underlying ‘small state’ philosophy, in particular the idea that government intervention serves to distort private markets. In contrast, potential drawbacks of schemes which replace public decisions with private ones include:

Reduced transparency and accountability in contracting process

Reduced transparency and accountability in delivery of service

Unpredictable take up and costs of service delivery

Inability to control quality or enforce broader public sector objectives (e.g. economic, environmental, social)

Poor market response, due to complexity and risks of schemes

Erosion of citizen confidence in public services, due to poor service delivery and/or confusion about the role of the State

Unfortunately, both the Green Deal and Verify vividly illustrate these problems. I discuss these in more detail in the paper, but will summarise here.

The Green Deal

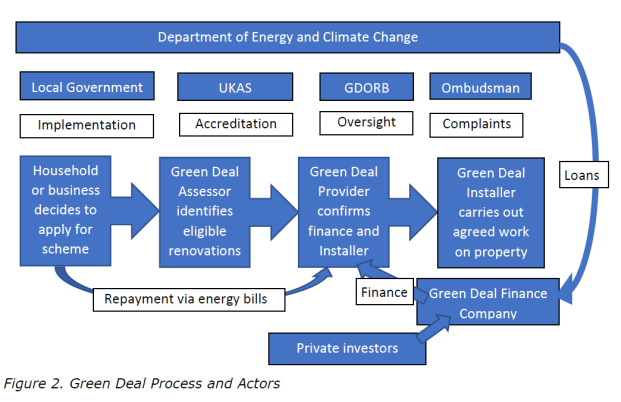

At its launch in 2011, the Green Deal was expected to support 14 million UK households and businesses to implement energy-efficiency measures. With a building stock far less energy-efficient than most other European countries, this was a key pillar of the coalition government’s climate change strategy. It wished to achieve this without significant public expenditure, by setting up a finance structure to allow householders to pay back the costs of improvements via energy bills. In 2015, the government ceased supporting the Green Deal Finance Company, effectively bringing an end to the scheme – with only 15,600 plans having been put in place (or just over 1% of the target). The Green Deal employed a complex structure of private and public actors, as illustrated in the below diagram. At its heart was a ‘golden rule’: the cost of renovations (including interest on money borrowed) could not exceed the projected savings on energy bills over the expected lifetime of the measures. This was intended to ensure the scheme was both attractive to households and financially viable for lenders.

The Green Deal quickly ran into a number of problems. Chief amongst these appears to be that the interest rates under the scheme were too high to make investment attractive to a large number of households. At 7-10%, interest rates significantly exceeded other forms of finance available to households, reflecting the need to attract private investors to the Green Deal Finance Company, as well as the overheads involved in determining eligibility, arranging the plans and installing measures. The complexity of the assessment and application process was also off-putting to many. Despite the intention to set up a trustworthy supply chain, multiple scams involving fake Green Deal assessors were reported. A short-lived grant scheme, the Green Deal Home Improvement Fund, provided cash incentives in an attempt to boost take-up – but this created uncertainty for households deciding whether to take on a loan. Surveys indicated that property owners were concerned about the need to gain permission from their mortgage lenders, as well as potential difficulties in switching energy provider or selling their property. These problems combined to make the scheme unattractive to householders. The lack of take-up for the scheme undermined the finance model. The expectation was that the Green Deal Finance Company would become self-financing, however its loan book never reached sufficient volume for this.[1]

Verify

As government services have digitised, the need to reliably authenticate citizens’ identity online has grown. Unlike many of their European neighbours, British citizens do not hold any universal form of identification.[2] The UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS) set out in 2011 to develop a platform to support identity assurance across central government. The services to be supported ranged from filing tax returns, to applying for or renewing driving licences, to accessing social welfare payments. Pre-existing methods of accessing government services online, such as the Government Gateway system used by HMRC, often required a code to be sent by post. Verify aimed to replace such systems, as part of the broader Government as a Platform (GaaP) programme. In its 2016 business case, GDS set a target for 46 government services to be accessible through Verify by March 2018, with 25 million users by 2020. Following a procurement exercise in 2014-15, seven companies were appointed to a framework agreement to provide identity assurance services under Verify. Providers would be paid a fixed fee for each user signing up, and a further fee for each year their profile remained active. By appointing multiple providers, the GDS aimed both to enable citizen choice and to encourage innovation within a competitive marketplace, in particular to develop alternative approaches to identity assurance. Figure 3 illustrates the structure of Verify.

Verify was intended to support the roll out of Universal Credit, the government’s major reform of social welfare payments. However, it ran into a number of problems which have severely limited its take-up. These problems arose both internally, with departments reluctant to commit to switching to the service, and externally, with providers experiencing difficulty in meeting the target verification rates. These problems became mutually reinforcing, as low success rates meant departments did not feel confident in abandoning older systems, and low demand meant providers could not afford to invest in more effective approaches.[3] Like the Green Deal, Verify’s financial structure relied upon a sufficiently high number of citizens using the service for providers to recoup their costs and make a profit. The cost to government was also intended to reduce as user numbers increased. By February 2019, just 3.6 million people had successfully used Verify. The verification success rate across all providers and all government services was 48%, compared to the 2015 projection of 90%.[4] In the case of Universal Credit, the verification success rate fell to 38% – reflecting the difficulty in providing digital identity assurance to those in greatest need of public services. Twenty government services currently use Verify, less than half the number expected by March 2018. At least 11 of these services can be accessed through other online systems. The low take-up means the ambition for Verify to be self-funding has not been met. The Cabinet Office has announced that it will stop funding the service in March 2020 – with the intention that the private sector will take over the service.

Conclusions

Both the Green Deal and Verify employed novel contracting arrangements which involved citizen choice. Although the primary aim was not to avoid application of the procurement rules, these schemes vividly illustrate the pitfalls of removing government from the decision-making process. In the paper I argue that future schemes need to be subject to more rigorous ex ante evaluation, and propose a number of ‘existential’ and more practical evaluation questions. Reflecting an underlying small-state philosophy, the Green Deal and Verify aimed to create competitive private markets for the provision of technically challenging services. The attraction is clear: where the ultimate beneficiary of a service is the citizen, surely removing an inefficient intermediary such as the state will yield better results?

As has been seen, the picture is not so simple. A contradiction seems to lie at the heart of these initiatives: if private decision-makers are best placed to choose and/or finance public services, then why don’t they do it without the need for elaborate state interventions which aim to create the correct incentives? With the legal environment encouraging further experimentation with such schemes, it is important to subject them to proper scrutiny, including on their ability to deliver much-needed environmental, social and innovation objectives. The paper is in draft form and I’ll be working over the summer to refine it – comments are very welcome.[1] In 2017 the GDFC was sold to private purchasers and has since recommenced lending to finance energy renovations – at higher interest rates.[2] The Identity Cards Act 2006 provided for the creation of a National Identity Register, biometric ID cards and a common travel document. However, this Act was repealed in 2010 due to widespread public concern about its scope and use, and the database was destroyed.[3] These problems can be discerned from the NAO and Public Accounts Committee reports on Verify published in 2019.

However, neither report appears to have taken evidence from providers involved in Verify. The NAO report does include a very moving piece of written evidence from a frustrated user, Mr. P.G. Slater, who states: “ I have a poor opinion of this Gov Verify system for all the hours of my time it has wasted, the inextricable complexity of the security, the fact that you have to deal with two organisations… who don’t seem to be able to coordinate help for users. Just to prove your identity. Ultimately, no system can ever really confirm who you are. Ironically, I still have an Identity Card from the 1950s which was issued when you were born, so that you could use the post-war rationing system.[4] NAO (2019) The verification success rate measures users who succeed in signing up for Verify in a single attempt, but does not indicate whether the user succeeds in accessing a government service. It also excludes users who drop out before finishing their applications.